Lately there has been a batch of talk about “(local) Government as a Platform” including blogs from Dave Briggs, Gavin Beckett, Mark Thompson, and others, with video clips from John Jackson and a slide deck from Methods Digital. This all links to recent blogging about single platforms for local government websites and digital in local government generally.

All of this made me reflect on two things – my original blog posts on the topic in 2012 (and whether what I’ve done since is consistent with that vision), and whether this is all really doing what it needs to in 2015, is it solving the problem that we need to solve today.

And, to be quite blunt, I think the answer to these questions are “meh” and “no”, respectively.

From 2012:

“Local Government (in this model) is a hub. It’s purpose is to connect people (and places) with needs to people with funding to people who can provide services to help under the governance and ownership of people with the political mandate to do just that – with the aim of improving the lot of the people and places under its jurisdiction.”

I would just like it to be noted that I was, and am still, being descriptive of the purpose of local government. That is, I was thinking local government IS a platform, not local government AS a platform. I was using this as a lens to try and make sense of the industry I work in, not as an explicit design of a possible future state, although it does imply some changes to the way we do things*.

Obviously things change and move on and I am not an exception to that, so I’m here and now asking myself how the above description stacks up with my current understanding and thinking it’s ok, if a bit granular. Clearly government of all kinds has the aim of connecting people and improving stuff (although those things aren’t usually so causally linked), that’s kind of obvious but it doesn’t quite get the point. What is the unique thing that government does that no other kind of business can do?

The short answer to this might be “user research”. Every council employs – by statute – at least a dozen people that do user research, they get performance managed every four years and regularly get fired if they are a bit crap. Our councillors don’t always use the same methods as professional user research teams but they are seriously committed and highly visible and work to the same ends.

Of course, plenty of commercial operations do user research as well, but the difference is that when councils (or indeed governments generally) do it then it is a public conversation. People canvas the views of local people about what their priorities should be, then formulate these views into policy documents (“manifestos”) and everyone gets to vote on which person and policy document is the best: the winner then gets to try and make these priorities a reality, with the conversations around this being made public immediately, and their policy work is scrutinised and held up to public account. If people don’t like the results then 4 years later they’ll be fired and another mixture of policy priorities will be voted in.

The GDS mantra since day one: “What is the user need?” – I would say that government exists to uncover and highlight the (sometimes rapidly) changing needs of its citizens and the places they live in via an ongoing public conversation. Local Government is a platform when – and only when – it enables those conversations and allows a variety of organisations to design services to satisfy those needs, but the choice and delivery of those services – including design decisions around digital services – is a tactical one. It’s the conversation that uncovers the needs that is core to Government, not the services.

So perhaps we don’t need to spend lots of money on new technology, we just need to listen to what people are already telling us and find better ways of reflecting it. Better conversations lead to better targeting of services (not just ours either) and, ultimately, better results.

For these reasons I think that the conversation about “local government as a platform” shouldn’t be a conversation about technology or even about business models, when it should be about democracy and finding ways to support the work of active citizens – our councillors, voluntary sector organisations, businesses, families and agencies – specifically linking them to data insights, and giving them direct control over more levers of power to make them more relevant and give them more power to uncover user needs.

In the process we need to become more platform-like – but by changing our working practices and culture, not just by installing software. We in local government need to be the platform, not just build it.

I want to blog a bit more about this in the coming weeks, but obviously would welcome the chance to broaden this conversation out. I’m an IT bod, not a political theorist.

* Specifically, articulating this description led me to do a number of things:

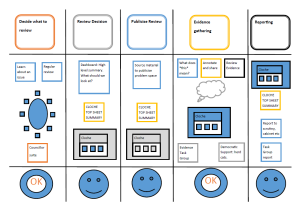

- look at the use of data and intelligence in this context, specifically to support councillors (with Lucy Knight, who is taking this forward)

- establish a local ODI Node to help the whole community benefit from public data resources

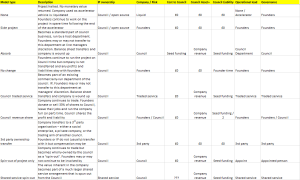

- look at prototyping different public business models

- support the implementation of integration technologies to help knit web services together

- specify open data and APIs in standard procurement specifications

- get involved in a small way in a number of specific procurements with the aim of improving the openness of the chosen solutions.